|

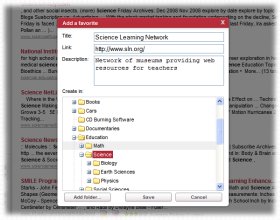

Education

Web

Dr. Rich's Page o' Math

vector007.com

Abiding Dave's Philatelic Glossary

science501.com Click here to go to science501.com.

englishrocks1.com Click here to go to englishrocks1.com.

englishrocks1.com Click here to go to englishrocks1.com.

Merit Badge Research Center

Welcome To Merit Badge Dot Com Continue Welcome To Click Here To Enter

The Human-Languages Page

June29.Com June29.Com Websites Welcome Welcome to June29.Com, a server committed to bringing quality and content to the Web. Are you part of the 99%? Find your percentage at What's My Percent. iLoveLanguages (formerly The Human-Languages Page) Web Spanish Lessons...

Curriculum Development: Curriculum Designers, Inc.

Heidi Hayes Jacobs Curriculum Designers is now Curriculum21 Curriculum Designers Inc. Heidi Hayes Jacobs CurriculumDesigners.com is now curriculum21.com. Please bookmark our new address: http://www.curriculum21.com. Click here to continue to curriculum21.com...

Tufts University: Simple Linear Regression

This Web Page has moved!!! The new URL is http://www.JerryDallal.com/LHSP/slr.htm Please update your bookmarks. Problems? Please let me know! Jerry (at) JerryDallal (dot) com

Kate Bayliss and Tim Kessler 15 Privatisation proponents m aintain that all basic services can be im proved through increased form s of com petition. In the case of utilities, they argue that com petition in the bidding process itself helps reduce utility prices for consum ers. In...

1

0

Kate Bayliss and Tim Kessler 15 Privatisation proponents m aintain that all basic services can be im proved through increased form s of com petition. In the case of utilities, they argue that com petition in the bidding process itself helps reduce utility prices for consum ers. In the case of health care, education, and electricity generation, privatisation advocates argue that consum ers benefit from direct com petition: low barriers to entry and the ability to choose am ong m ultiple

8

0

http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=8

www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=8

erous form s of m arket-based reform s, the m ost basic distinction is between <span class="highlight">com</span> m ercialisation and privatisation. Broadly speaking, commercialisation is the process of transform ing a transaction into a <span class="highlight">com</span> m ercial activity, in which goods or services acquire a m onetary value. U nder this approach, a service provider seeks to cover m ost or all of its costs directly from individual (or household) service users. The reduction or elim ination of subsidies is a <span class="highlight">com</span> m on form of <span class="highlight">com</span> m ercialisation

9

0

http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=9

www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=9

bitious expectations of its prom oters. <span class="highlight">Com</span> m ercialisation <span class="highlight">Com</span> m ercialisation often signals an effort to cut fiscal deficits or generate m ore financial resources for the service itself. It can also discourage profligate use (as for exam ple in the water sector). <span class="highlight">Com</span> m ercialisation is perceived as an economic solution to the problem of scarce resources. Finance m inistries often prom ote <span class="highlight">com</span> m ercialisation to slash subsidies. Fiscal pressures can be so strong that financially viable and well-perform

14

0

http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=14

www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=14

12 International Poverty Centre W orking Paper nº 22 profitability for private generators, and can expose governm ents to huge fiscal risks and losses that cannot be restructured through re-negotiation. In other words, PPAs can virtually elim inate the prospect of <span class="highlight">com</span> m ercial risk. For exam ple, a case study of energy sector reform in Bangladesh concludes: “From a policy perspective, such long term contractual obligations, especially overly-generous ones, are an inadequate substitute for a proper

15

0

http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=15

www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=15

Kate Bayliss and Tim Kessler 13 Private providers have strong incentives to lim it what regulators know about the utilities they operate. According to a W orld Bank researcher on infrastructure: “The fundam ental problem of regulation is one of asym m etric inform ation between the regulated <span class="highlight">com</span> pany and the regulatory agency. The regulated <span class="highlight">com</span> pany will have a strong incentive to abuse [its] strategic advantage by under-supplying inform ation or distorting the inform ation supplied” (Foster

16

0

http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=16

www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=16

for-profit private sector are involved in unnecessary procedures, such as high rates of caesarian sections, unwarranted tests and surgeries (W orld Bank 2004). In the water sector, regulators are usually unable to <span class="highlight">com</span> pel firm s to disclose inform ation about perform ance or prices. Yet without such data, it is not possible to verify, for exam ple, if cost-based tariff increases are justified. In G abon, the regulator found it difficult to m onitor the activities of the private operator: “In the absence

17

0

http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=17

www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=17

Kate Bayliss and Tim Kessler 15 Privatisation proponents m aintain that all basic services can be im proved through increased form s of <span class="highlight">com</span> petition. In the case of utilities, they argue that <span class="highlight">com</span> petition in the bidding process itself helps reduce utility prices for consum ers. In the case of health care, education, and electricity generation, privatisation advocates argue that consum ers benefit from direct <span class="highlight">com</span> petition: low barriers to entry and the ability to choose am ong m ultiple

18

0

http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=18

www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=18

private operators (G uasch 2004). The high level of renegotiation underm ines the nature of the <span class="highlight">com</span> petitive bidding process. W hile renegotiation m ay be expected in a long term project where conditions change over the years, evidence from Latin Am erica indicates that renegotiation takes place after an average of just 2.2 years from the start of the contract (Estache et. al. 2003). The need to m inim ize risks is leading both governm ents and private firm s to adopt short- term m anagem ent contracts

21

0

http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=21

www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=21

Kate Bayliss and Tim Kessler 19 The challenges of creating well-functioning electricity generation m arkets are dem onstrated m ost powerfully in developed countries, where regulatory institutions are m ore experienced and have far greater financial and personnel resources than in poor ones. According to the U S N ational <span class="highlight">Com</span> m ission on Energy Policy, “Electric industry restructuring [in the U S] has derailed. The m assive blackout of August 14, 2003 certainly was not needed to underscore the

28

0

http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=28

www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=28

South Asia 51 14.98 Sub-Saharan Africa 38 7.64 Total 748 100.00 Adapted from Izaguirre (2005). M oreover, m uch of the investm ent that is privately financed <span class="highlight">com</span> es from taxpayers or end users. As discussed earlier, infrastructure projects are underwritten by a governm ent <span class="highlight">com</span> m itm ent to pay for a fixed output at a price agreed on in foreign exchange. W here construction is carried out by the private sector, the governm ent still has to pay – although paym ent m ight be deferred or fall under an

35

0

http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=35

www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=35

term s of quantity of docum entation, but in term s of accessibility to regular citizens. Contrary to popular slogans, inform ation is not always power. Service providers that do not wish to be scrutinized m ight respond to inform ation requests by dum ping m ountains of data on the public, which can confuse or intim idate citizens and m ake action difficult. Inform ation about utilities in its purest form – raw data – will not be <span class="highlight">com</span> prehensible to m ost people. Efforts to synthesize, abridge and

39

0

http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=39

www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=39

or private, there is no substitute for political <span class="highlight">com</span> m itm ent to dedicate public resources toward these groups. Perhaps m ore im portantly than their econom ic weaknesses, <span class="highlight">com</span> m ercialisation and privatisation reduce the political pressure on governm ent leaders to take seriously the need to equitably allocate budgetary resources. W hen user fees contribute to self-financing or a long-term concession sim ply transfers responsibility from the State to a private <span class="highlight">com</span> pany, politicians are no longer

47

0

http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=47

www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper22.pdf#page=47

NOTES 1. For a detailed update on progress toward each of the M D G s broken down by geographic region, see D FID (2005). 2. A <span class="highlight">com</span> m on exam ple is a ‘pass-through’ on costs, under which a pre-set form ula adjusts tariffs autom atically so that specified cost changes, e.g., oil prices, key inputs, and exchange rate fluctuations, are im m ediately reflected as increases in the tariff, typically without regulatory review. The purported goal of autom atic tariff adjustm ent is to provide a secure

36 International Poverty Centre W orking Paper nº 26 Sim ilarly, we can calculate the contribution of each incom e com ponent to the growth rate of total per capita incom e: ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )4321 CCCC ttttt γγγγγ +++= (A.3) Subtracting (A.3) from (A.2) gives...

1

0

36 International Poverty Centre W orking Paper nº 26 Sim ilarly, we can calculate the contribution of each incom e com ponent to the growth rate of total per capita incom e: ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )4321 CCCC ttttt γγγγγ +++= (A.3) Subtracting (A.3) from (A.2) gives the contribution of each incom e com ponent to the inequality of total per capita incom e. ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )4*3*2*1** CgCgCgCgg ttttt +++= (A.4)

29

0

http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper26.pdf#page=29

www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper26.pdf#page=29

Grow th rates by non-labour <span class="highlight">com</span> ponents Non-labour income Period Labour income Social security Other non-labour Non-social income Total income Actual growth 1995-2004 -1.49 3.25 5.77 -2.43 -0.63 1995-2001 -1.30 4.69 0.73 -1.23 -0.30 2001-2004 -2.05 0.86 13.26 -3.69 -1.35 Pro-poor growth 1995-2004 -0.73 3.12 29.94 1.43 0.73 1995-2001 -0.97 2.56 25.50 4.41 0.10 2001-2004 0.97 3.90 35.21 -1.97 3.07 Inequality 1995-2004 0.76 -0.13 24.17 3.86 1.36 1995-2001 0.32 -2.13 24.77 5.64 0.40 2001-2004

30

0

http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper26.pdf#page=30

www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper26.pdf#page=30

28 International Poverty Centre W orking Paper nº 26 contribution is particularly high in the latter period 2001-04. W hile non-social incom e appears to play a sm aller role in reducing inequality, the net im pact of social security has been quite im portant. D uring the first period (1995-2001), the net effect of social security resulted in an increase in inequality. Its net contribution on inequality was greater than the net contributions by the other two <span class="highlight">com</span> ponents. Nevertheless, the sum of the

35

0

http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper26.pdf#page=35

www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper26.pdf#page=35

Nanak Kakwani, M arcelo Neri and H yun H . Son 33 APPEND IX SH APELY D ECOM POSITION TO EXPLAIN CONTRIBU TIONS OF INCOM E <span class="highlight">COM</span> PONENTS FOR PRO-POOR GROWTH Suppose there are four incom e <span class="highlight">com</span> ponents which include: X1t: Per capita labour incom e at year t X2t: Per capita social security incom e at year t X3t: Per capita cash transfers at year t X4t: Per capita non-social incom e at year t Total per capita incom e at year t is thus the sum of the four individual incom e <span class="highlight">com</span> ponents

38

0

http://www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper26.pdf#page=38

www.undp-povertycentre.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper26.pdf#page=38

36 International Poverty Centre W orking Paper nº 26 Sim ilarly, we can calculate the contribution of each incom e <span class="highlight">com</span> ponent to the growth rate of total per capita incom e: ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )4321 CCCC ttttt γγγγγ +++= (A.3) Subtracting (A.3) from (A.2) gives the contribution of each incom e <span class="highlight">com</span> ponent to the inequality of total per capita incom e. ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )4*3*2*1** CgCgCgCgg ttttt +++= (A.4)

|